US households’ balance sheets might not be as healthy as experts think.

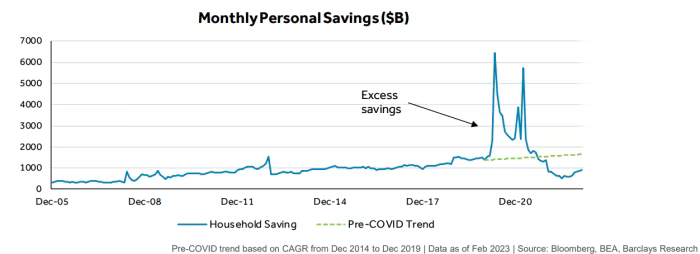

That’s what Barclays argues in a recent note, at least. Household finances have been strong for years after US government took an aggressive response that shielded Americans from the worst impact of Covid-19 lockdowns and left them flush with cash. Now, while companies are still hiring and there are few obvious signs of strain, Americans’ monthly personal savings have started to lag:

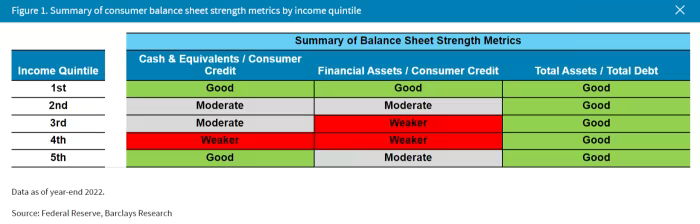

On closer look, “middle class balance sheets [now] look weaker than broad metrics suggest,” write Barclays strategists in a recent note.

They continue:

As might be expected, the balance sheets of first quintile (highest income) consumers appear to be in great shape. Perhaps less intuitively, we find that the balance sheets of fifth quintile consumers (lowest income) are also in good shape on a historical basis. Second quintile consumer balance sheets appear modestly improved, while third and fourth quintile balance sheets appear notably weaker on a historical basis.

That means the lower-middle and, uh, middle-middle classes are getting squeezed.

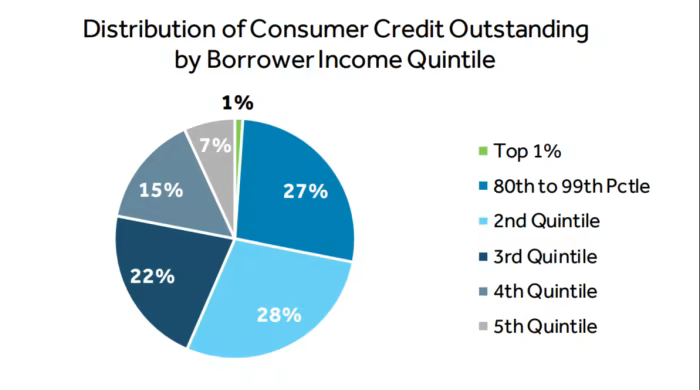

This matters because the market for bonds backed by consumer loans — credit cards, auto loans and the like — turns on the strength of American borrowers’ finances. If consumers can afford to keep paying their car loans, for example, all of the investors who own auto ABS will keep getting paid in full. If enough of those car borrowers stop paying, it kicks off a complex process that shuts down cash flows to some investors to protect cash flows to others.

Those tiers of income make up 37 per cent of outstanding US consumer credit (securitised and not), Barclays finds:

There are also some interesting offsets to the weaker balance sheets of the US’s middle and lower-middle classes:

While measures of financial assets relative to non-mortgage consumer credit show mixed results across consumer income quintiles, measures of total assets (including real estate) relative to total debt appear historically elevated for each income quintile. This means that 1) homeowners are faring much better than renters across the board . . . . . . and 2) in an environment of tightening consumer credit availability, elevated inflation, and lower savings rates, we believe middle-class borrowers may turn to home equity as a source of liquidity (pressuring home prices and, thus, a core source of wealth for the middle class) . . .

Broadly, Barclays doesn’t say it expects a wave of consumer-loan defaults any time soon.

And while they know that middle-class Americans make up a healthy share of borrowers, they can’t say which specific markets face the most risk from a middle-class crunch:

Unfortunately, we have not come across robust data sets showing borrower profile by income in securitizations. Accordingly, it is a bit difficult to extrapolate what the weaker middle class borrower means for prime auto vs. subprime auto vs. consumer loan vs. credit card fundamentals, etc . . . There is a correlation between FICO and income (see chart below), but we find it difficult to extrapolate this into lending segment relative value beyond the fact that we think more experienced lenders will fare better.

This report is intended more to capture the fact that broad metrics of consumer balance sheet strength may not be indicative for every US consumer, and that there is, in fact, balance sheet weakness across some consumer income segments.

Here’s that credit-rating chart mentioned by the bank:

Still, they argue that the consumer-loan ABS market isn’t pricing in the full risk of the environment. So while those securities are trading at lower valuations (and higher relative yields) than, say, loans against wireless-service towers or tax liens, Barclays says that investors aren’t compensated for the full extent of the consumer risk. They recommend clients look at other sectors instead:

In terms of ABS relative value, we favor diversifying away from profiles more sensitive to consumer credit performance, and favor investing in less correlated, more esoteric sectors . . . Within more consumer-credit-sensitive ABS, we favor shorter structures, and lenders with cycle-tested performance history that may be able to more adeptly navigate a strained environment for the middle class consumer.

Those “more esoteric” markets mentioned above include those for “structured settlements, digital infrastructure, [and] tax liens”.

Another caveat: even if consumer loans aren’t attractive compared to other ABS, they could easily hold up better than markets like corporate bonds and commercial real estate, Barclays says.

From Barclays:

Unless consumer health meaningfully underperforms expectations vs. other areas (e.g., corporates, CRE, home values, etc…), short, de-leveraging consumer ABS may be a good sector for investors worried about continued spread volatility.

The pressure on home values may be fueled by the middle-class consumer’s struggles, as the bank writes elsewhere in the note:

In the case of home equity and home prices… we recognize that there are many ways to unlock home equity — e.g., cash out refis, HELOCs, outright home sales, etc . . . In a higher rate environment, HELOCs and cash out refis have become less attractive. Accordingly, if the middle class consumer is under pressure, we think outright home sales may be the primary way of unlocking home equity, and this may pressure home prices.

Falling demand for mortgage-backed securities may not help either.

Source: Financial Times