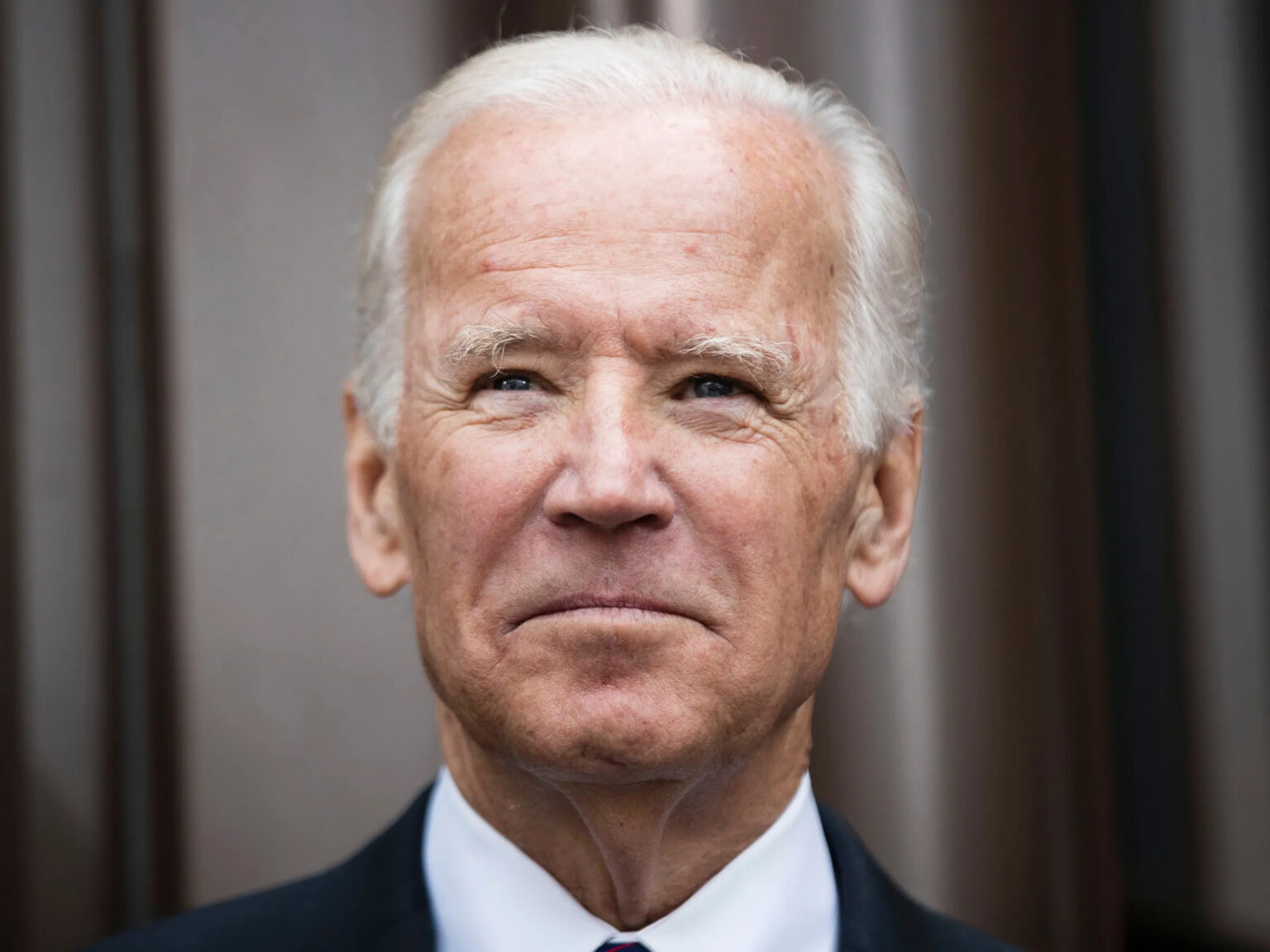

President Joe Biden bipartisan nature is being tested as campaign season begins.Carolyn Kaster

President Joe Biden says he’s willing to work with GOP House Speaker Kevin McCarthy, issuing a formal statement to congratulate him and personally calling the California lawmaker after he secured the job. He had Senate Republican Leader Mitch McConnell with him in McConnell’s home state of Kentucky earlier this month as the two political foes touted the work being done because of the Bipartisan Infrastructure Act. The president frequently name-checks Republicans when he signs a bill or hosts an event, thanking them for their work.

That’s been a typical approach for Biden, who continues to insist – despite deep partisan divisions across the country and in Washington – that the two parties can go back to the traditions of an earlier era, such as when he was a senator, when lawmakers would squabble but ultimately compromise for the good of the country.

But since the electoral calendar moved into early presidential campaign season, Biden’s darker, more politically aggressive side has emerged with a vengeance. He frequently slams “MAGA Republicans” and his spokesmen have slammed the McCarthy-led GOP’s plans to “protect rich tax cheats” and cut funding for Social Security and Medicare.

From the dignified podium in the White House briefing room, press secretary Karine Jean-Pierre said House GOP leadership had “handed over the keys” to members who “have promoted violent rhetoric and conspiracy theories” and openly wondered what “secret deals” McCarthy had made with them to get their votes for speaker on the 15th ballot.

Voters are likely to see both sides of Biden as the 80-year-old president prepares for an expected announcement that he will run for reelection. Privately, Democrats say they don’t expect Biden to be able to get much passed by Congress in the next two years, since House Republicans are eager to use their new majority to stop Biden’s agenda and investigate him, his family and his Cabinet.

That leaves Biden to do two somewhat contradictory things: remind Americans of the substantial list of accomplishments he racked up, often with bipartisan support, while also casting the House GOP in particular as the source of political evil.

“I think it’s important for him to do both,” says Rich Luchette, a Capitol Hill veteran who is now a Democratic strategist with Precision Strategies. In 2020, running against Donald Trump was enough, but “when the president is on the ballot in 2024, the American people are going to judge him more on his record in the last four years than they are (his comparison) with Trump.”

That means navigating a complicated relationship with McCarthy, who has added complications of his own. The speaker made a number of promises to get the job, including agreeing that a single House member could call a “no-confidence” vote and presumably oust him.

And it puts McCarthy, second in line to the presidency, in an unusually vulnerable position, since any of the 20 Republicans who at various times withheld their votes for McCarthy as speaker could threaten to force him out of the role he has wanted for decades.

“They are intent on bringing things down,” Matt Bennett, senior vice president of the centrist group Third Way, says of the rogue House Republicans. “You can’t count on McCarthy at all. He’s weak. It’s not clear what’s in his heart and it’s not important. It’s what he’s doing that matters, and he’s empowered the crazies.”

The best-case scenario for the White House is that Biden works with McConnell – a fierce Republican who nonetheless has shown a willingness to permit some Biden bills to get a vote – and puts pressure on McCarthy to do the same, at least on occasion.

The middling scenario is that Biden endures two years of House investigations into his family and himself, gets virtually nothing of substance passed, and threatens to veto GOP items such as national abortion restrictions, cuts to Social Security and Medicare and a 30% national sales tax.

This week, the worst-case scenario for Biden, Congress and the global economy emerged: The nation reached its debt limit, putting the United States on a path to devastating financial default unless Congress acts.

If the universal goal were to avoid a panic on Wall Street, the potential loss of millions of jobs and a ripple effect that would hurt economies around the world, the choice would be easy, experts say. Congress would merely raise the debt limit (which applies to obligations the nation has already made or spent and does not give a “blank check” for further spending).

But politically, the goals are different for a contrary group of GOP lawmakers whose constituents incorrectly see raising the debt ceiling as a license to increase new spending.

“Politicians behave (according to) their incentives. If you’re in elected office, you can’t get more elected – you can only get unelected,” says Peter Loge, a former senior Capitol Hill staffer who is now an associate professor of media and public affairs at George Washington University. “The politics of the debt ceiling and Congress is not about the American people or the debt,” he says. “It’s about small elections involving a relatively small group of people.”

For individual lawmakers in Trump-loyal districts, that means there’s no point in trying to get another 10% of the vote from moderates when hanging onto the base that elected them will due, Loge says. And for McCarthy, the loss of support of just a handful of Republicans could lose him his job.

“What McCarthy wants to do is to be seen to be doing the things that he thinks will prevent him from losing power,” Loge says.

Democrats say it’s actually a political gift if House Republicans use their majority advantage to pass “message bills” (such as abortion restrictions, eliminating the IRS and other measures that would die in the Senate or be vetoed) and conducting investigations. Merely running against Biden – and offering little about what they would do for the American people – resulted in a disappointing midterm election night for the GOP, Democrats say.

That would merely provide more political fodder for Biden, giving him someone convenient to blame if and when he can’t get the House to pass his agenda items, experts say. But the debt ceiling would be a too-dangerous tool in that political arsenal, they add – meaning Biden might need to play both sides of his political character to the GOP leadership.

“How McCarthy navigates this is the real question,” says Kyle Herrig, executive director of the Congressional Integrity Project. “If the choice is between the global economy and losing your speakership,” he says, the stakes are high.

Source: us news